Introduction

Opioid analgesics are essential and irreplaceable drugs in the treatment and control of moderate to severe pain. As a result of the epidemic situation experienced in the United States, it is essential to offer health professionals and members the recommendation guidelines, recently published by SEMDOR, on how to make good medical use of opioid drugs to treat chronic non-oncological pain (persistent or recurrent) (1). These guidelines provide specific guidelines for addressing the selection of patients eligible for opioid treatment, as well as for initiation, follow-up, monitoring, or discontinuation of treatment. The most relevant points of these guidelines were the following:

1) all patients are entitled to pain relief; 2) opioid drugs are indispensable and irreplaceable to treat moderate-severe pain; 3) the management of these drugs must be carried out by professionals adequately trained in pain as well as in control and monitoring of opioids; 4) prior evaluation of the patient and the type of pain will determine if he or she is eligible for opioid treatment; 5) the selection of the most appropriate opioid will be made based on patient profile (type of pain, co-medications, comorbidities) and the product (molecule, formulation, mechanism of action and pharmacokinetic profile); 6) the start will be made with a test phase; 7) follow-up will be frequent especially at the beginning of treatment and then every trimester; 8) the evolution of pain, adverse effects, dose-frequency compliance by the patient, warning signs of abuse and renal function as well as co-morbidities and poly-medication should be monitored; 9) these drugs must be part of a multimodal strategy; 10) good medical use of opioids reduces the risk of adverse effects; 11) adverse effects should be anticipated and treated as far as possible. Additionally, recommendations are established on the responsibilities and resources that affect doctors, pharmacists and patients. Finally, points of improvement are provided that must be implemented in relation to the management of opioid drugs at the level of health systems to improve the measurement systems of prescriptions and adverse events, optimize dispensing with the use of new technologies, advance in multidisciplinary coordination and establish quick and simple means to communicate clinical guidelines such as the one presented here. In order to quantify the degree of agreement that SEMDOR members have with the published guidelines, an online survey was carried out, the results of which are presented in this article.

Objetives

Se The following objectives were set:

1. Primary objective: to quantify the relevance of opioid medicines and the level of agreement of SEMDOR members regarding clinical practice recommendations for the use of these medicines in the treatment of moderate-intense pain.

2. Secondary objectives:

2.1. Identify barriers to opioid medicines prescription in Spain

2.2. Estimate the number of patients treated with these medicines and the percentage of them who have tolerance, dependence or addiction.

2.3. Collect suggestions on topics related to opioids that SEMDOR members consider most appropriate and necessary to be included in the next training events of the society.

2.4. Know the willingness of members to participate in a retrospective registry of patients treated with opioids.

The results corresponding to the primary objective are presented in this article while the results corresponding to the secondary objectives will be presented in a later article.

Metodology

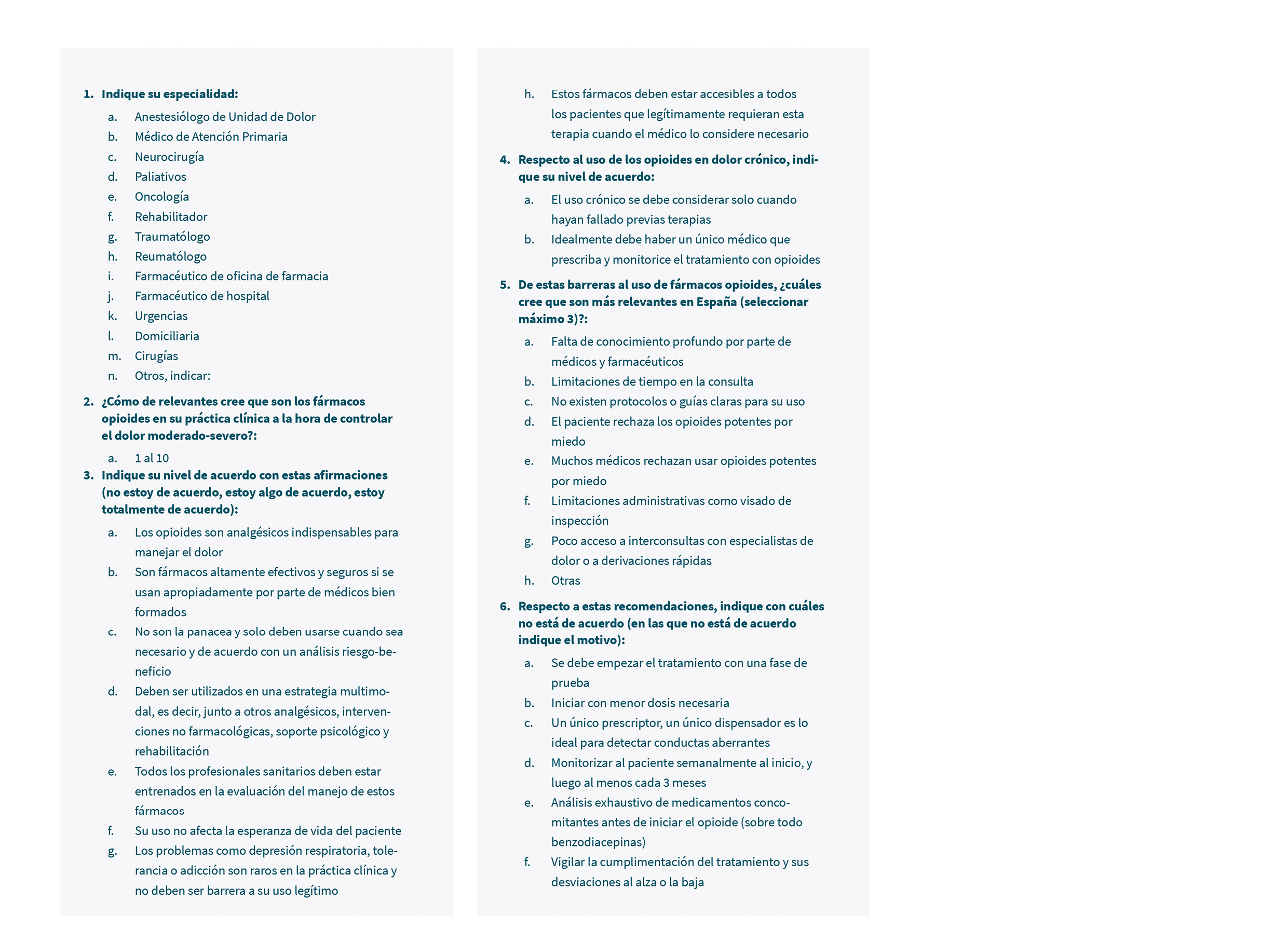

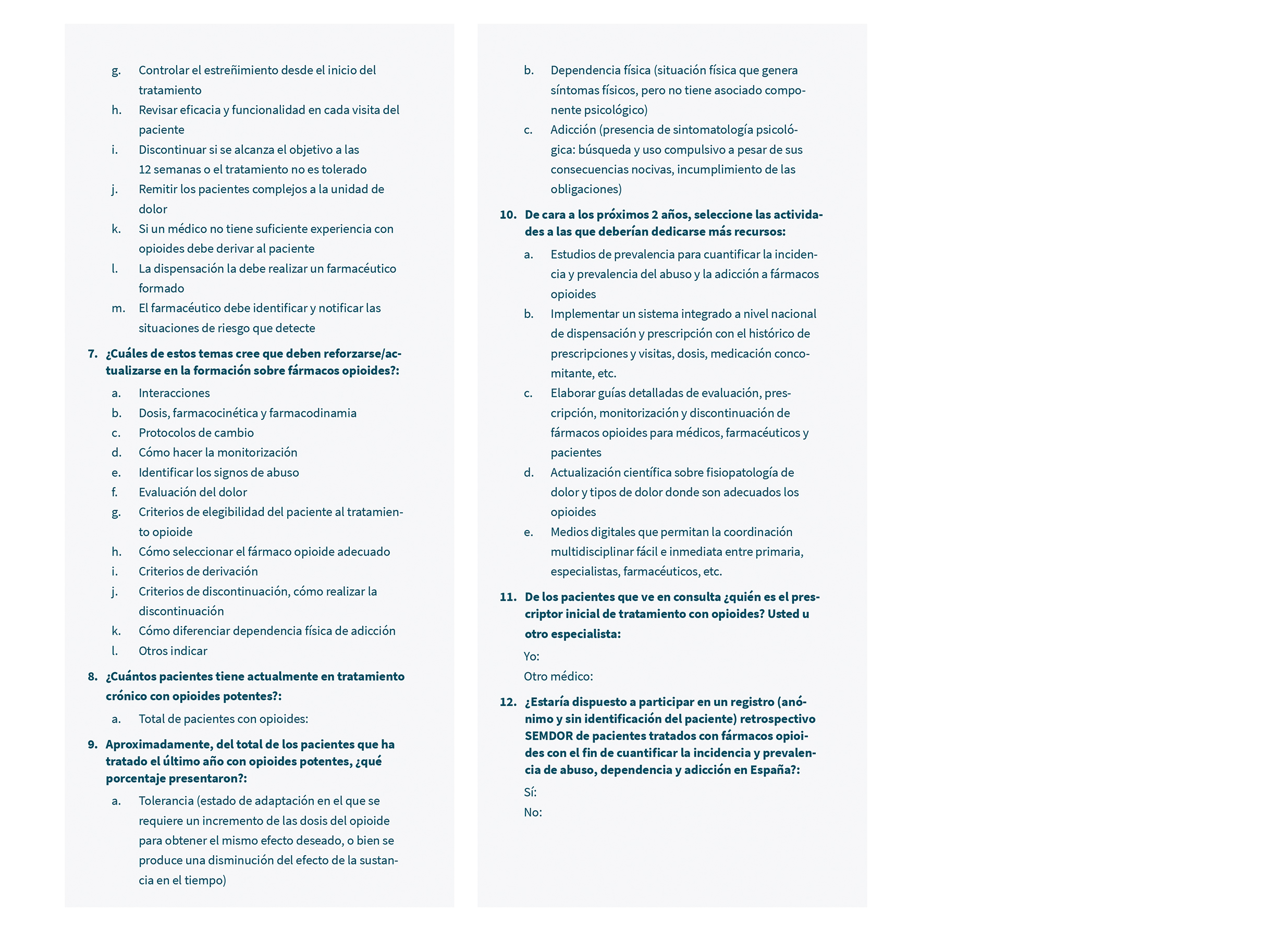

A working group was established within the SEMDOR opioid group formed by the same authors who were in charge of the elaboration of the treatment guidelines. A survey was designed with 12 closed and open questions in which the following aspects were assessed: relevance of opioid drugs in clinical practice, level of agreement with the recommendations and positions of the SEMDOR guidelines, identification of barriers to the prescription of these drugs in Spain, topics that must be reinforced or updated in the training on these drugs, number of patients treated and percentage with tolerance, dependence or addiction and activities that should be developed in SEMDOR during the next 2 years in relation to opioids. A first draft of questionnaire was made based on the recommendations included in the guidelines. This draft was reviewed and agreed upon by the members of the working group. The questionnaire was distributed by digital means to all 601 SEMDOR members for this, the collaborating company Axis Pharma S.L. carried out the programming of the questionnaire on its online platform and generated a link that was distributed by the technical secretariat of SEMDOR to all the members. The platform was automatically programmed to avoid duplication. The size of the universe was defined as any SEMDOR members. the answers were collected on an online platform and the analysis of results was carried out using the XLSTAT program. The t student was used in the statistical analysis to evaluate the significant differences. The programming of the questionnaire, the data analysis and report were carried out free of charge by the company Axis Pharma. The collection of responses was carried out anonymously and only personal data was collected from those who declared that they were willing to participate in a future patient registry, so that SEMDOR can contact them when said registry is launched. In order to be able to make comparative analyses, the sample was segmented into 3 specialty groups: Anesthesiologists, Primary Care and Rest. Annex 1 shows the questionnaire used.

Results

Sample size and participant’s profile

A total of 91 participants answered the survey of which only one was discarded because there were incoherent or doubtful answers. The sample used in the data analysis was therefore

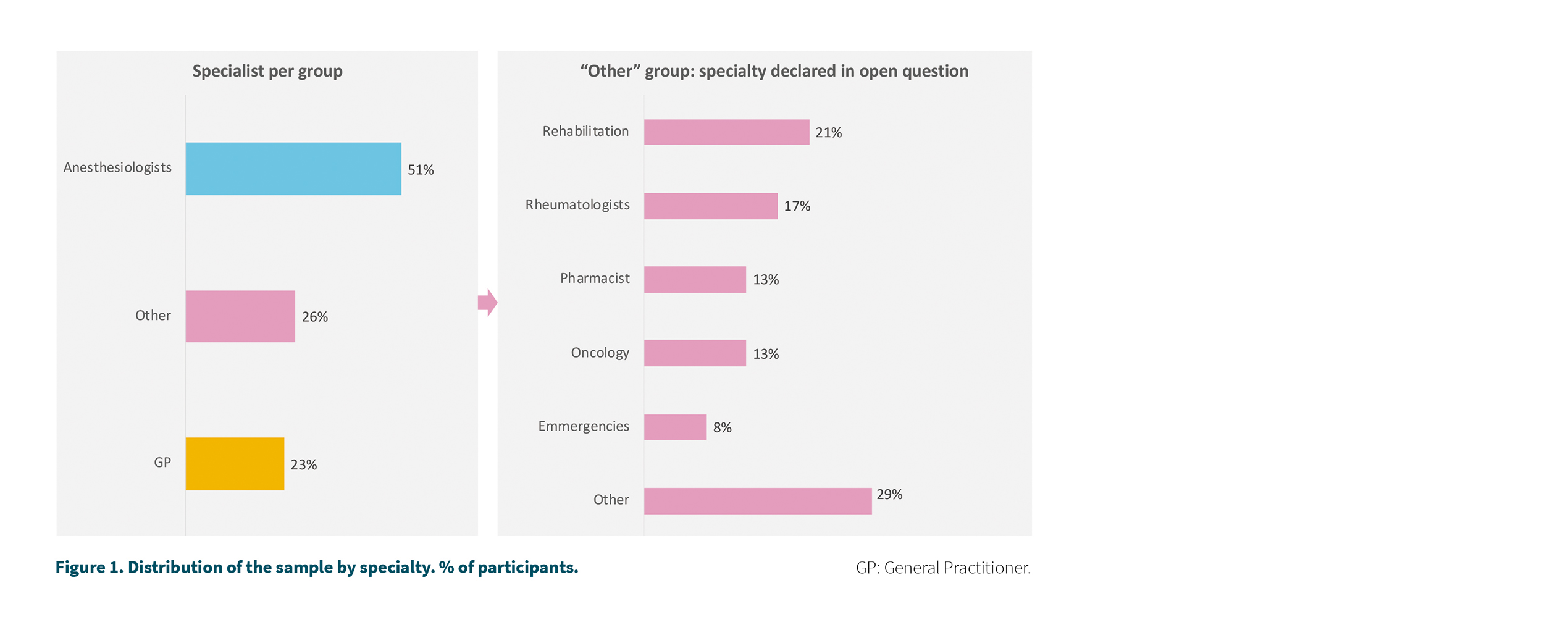

90 participants, which represents 14.9 % of the universe equivalent to a 9.5 % margin of error to 95 % confidence. Figure 1 shows the distribution of the sample by specialty. The 90 participants answered all questions except for questions related to the number of opioid patients (n = 84) or the percentage of self-initiated patients (n = 87) or specialty who started treatment (n = 64). The corresponding sample size has been indicated in the corresponding figures.

The majority of participants were anesthesiologists (51 %) followed by primary care physicians (23 %). In the group of other specialties, rehabilitators and rheumatologists stand out (Figure 1).

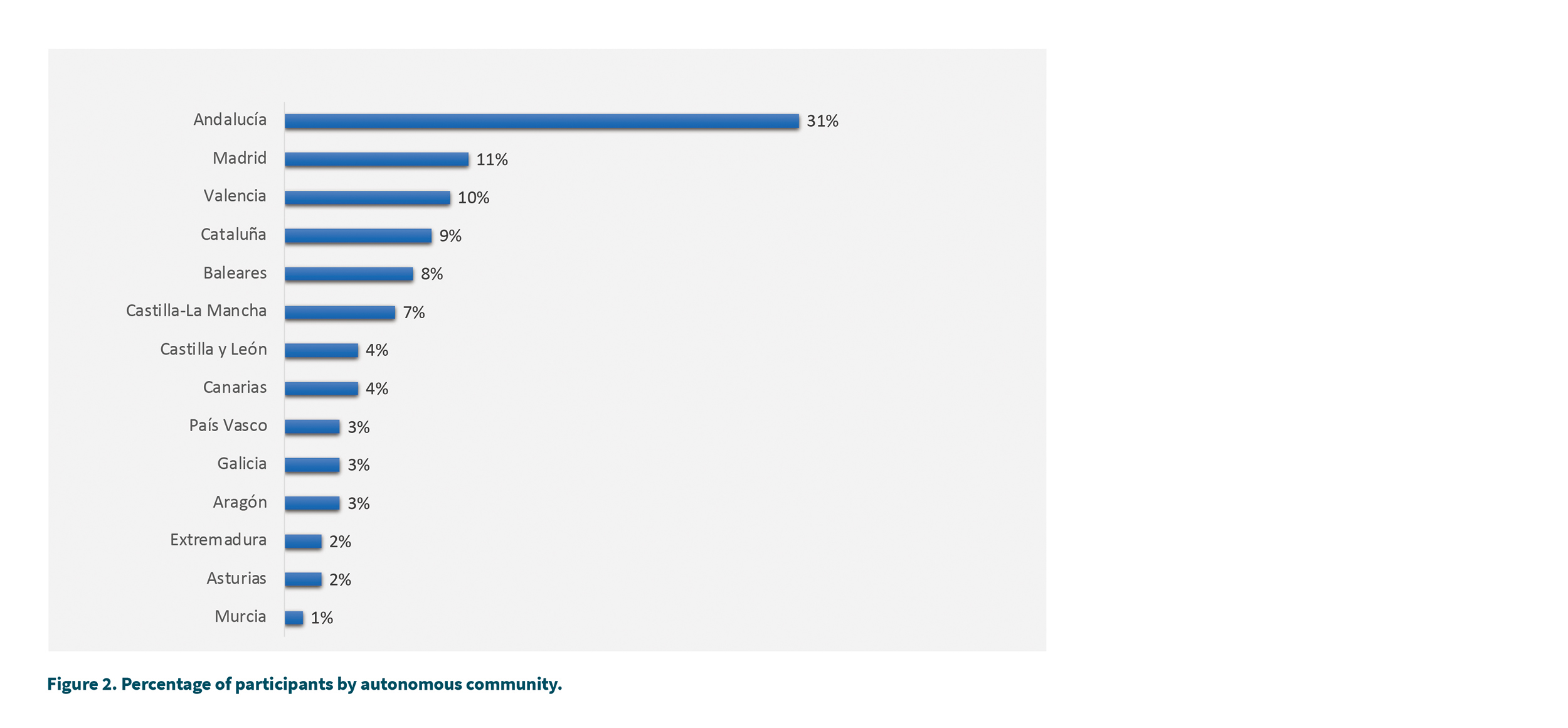

Regarding the geographical distribution of the sample (Figure 2), the 5 regions with the most participants were: Andalusia (31 %), Madrid (11 %), Valencia (10 %), Catalonia (9 %) and the Balearic Islands (8 %).

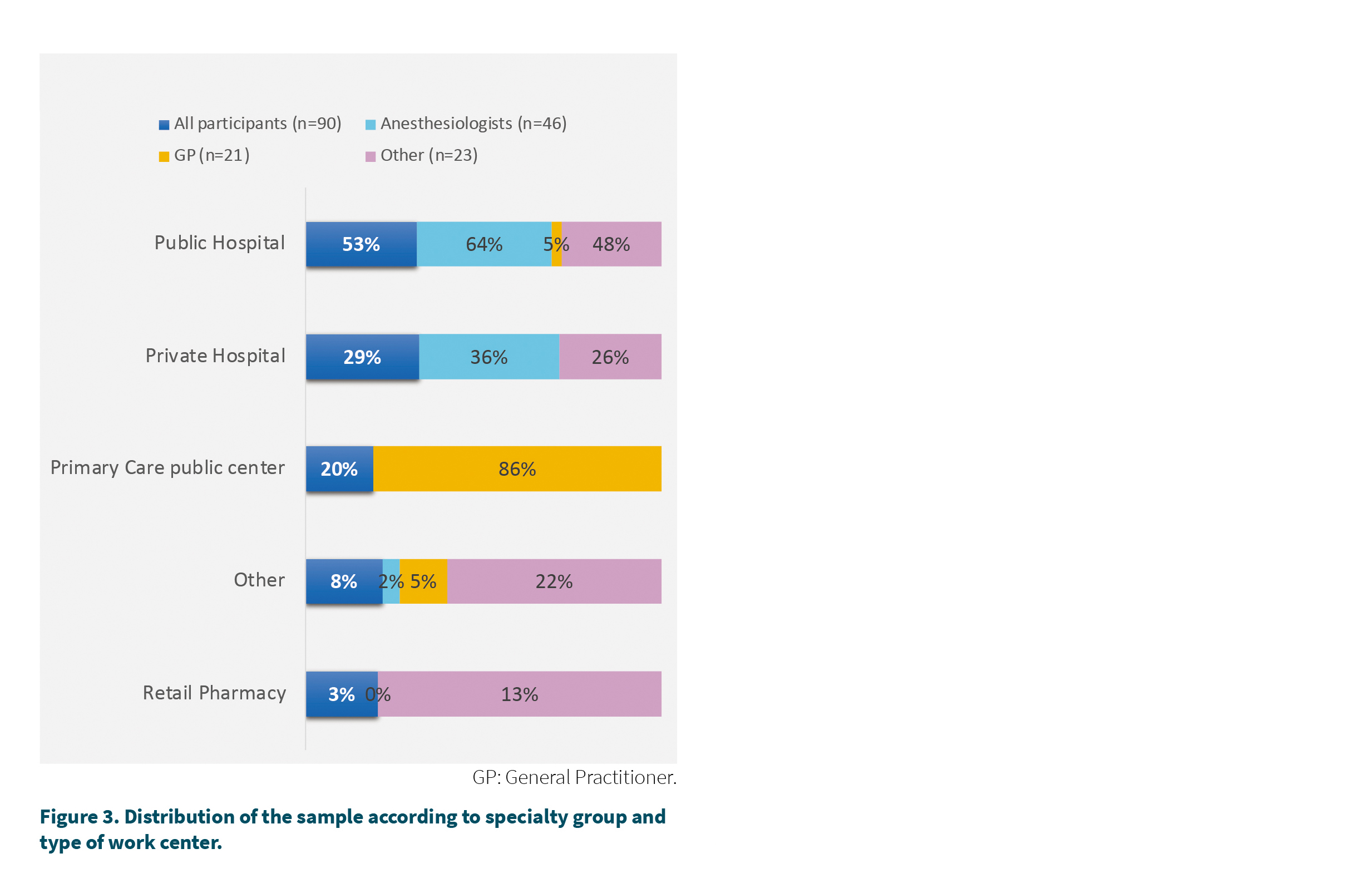

Regarding the type of center in which the survey participants work (Figure 3), the majority declared working in a public hospital (53 %) while 29 % declared working in the private sector and 20 % in a public ambulatory center.

Relevance of opioid drugs

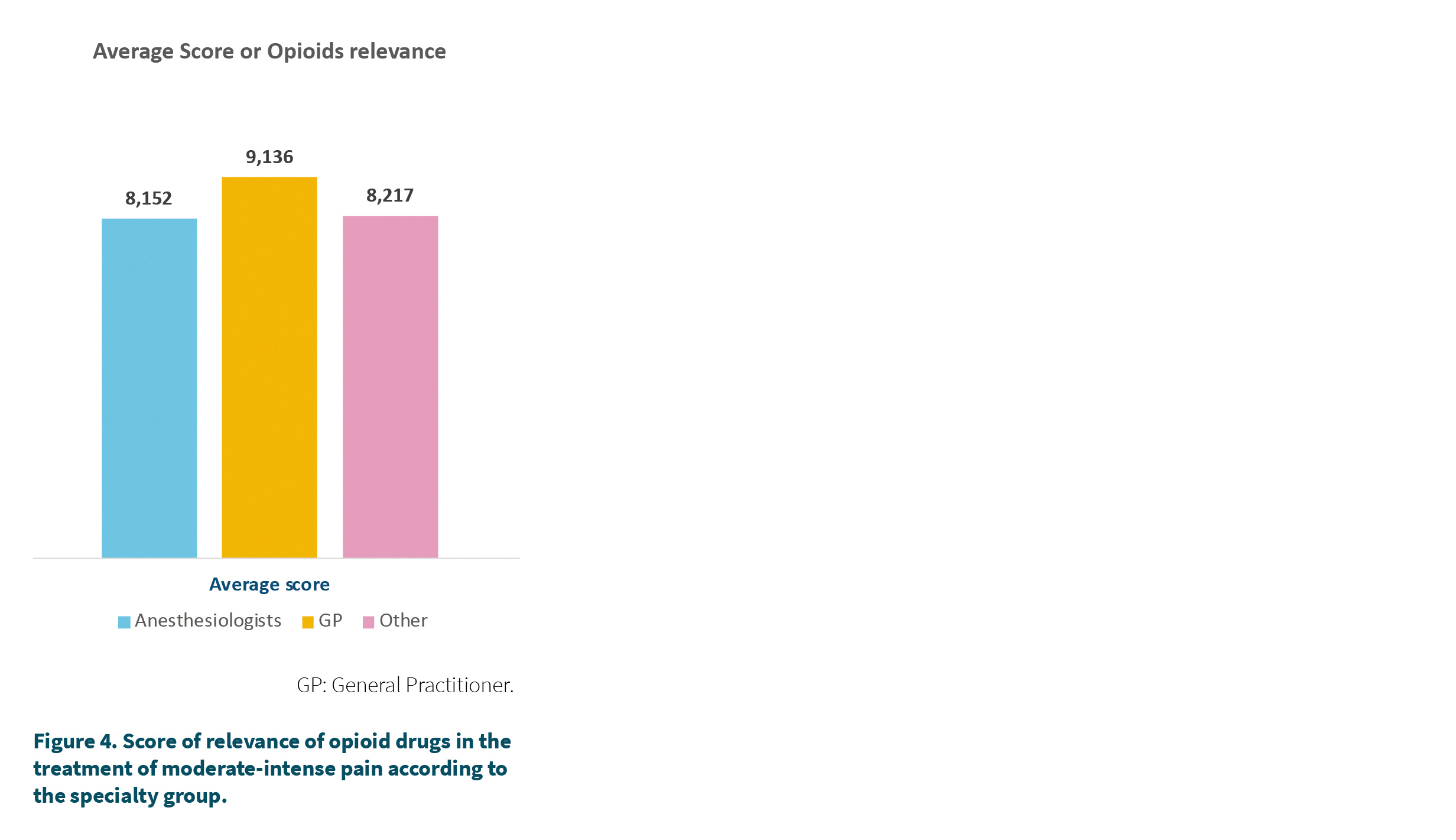

Participants were asked to rate from 1 to 10 the importance of opioid medicines in the control of moderate-intense pain, with 10 being equivalent to very relevant and 1 to nothing relevant. The mean score was 8.4 out of 10. 74 % of the professionals considered that the relevance was equal to or greater than 7 out of 10. Figure 4 shows the relevance scores according to the specialty group where greater relevance was observed in the primary care group (GP), which scored with an average score of 9.4 out of 10, this score being significantly higher than that of anesthesiologists (8.2). The group of other specialties also scored lower than the GP but the difference was not significant. 90 % of the GPs reported a score equal to or greater than 7 or more versus 67 % of the anesthesiologists or 74 % of the rest of the specialties.

Level of agreement with SEMDOR statements and recommendations

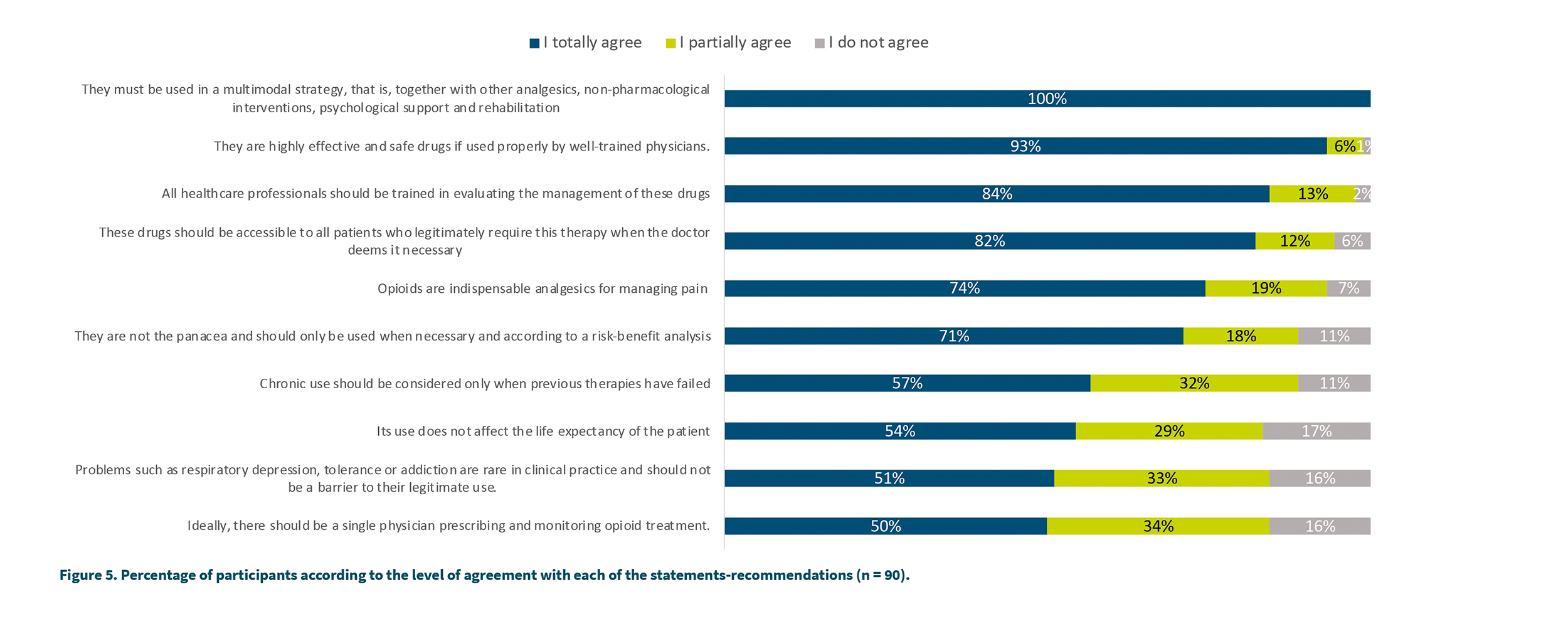

Study participants were asked to report their level of agreement with the recommendations and statements that have been included in the recently published SEMDOR recommendation guidelines (1). To do this, a choice was made between 3 options: I totally agree, I agree somewhat or I do not agree. Figure 5 shows the results.

The highest level of agreement (100 %) was reached regarding the need to use opioid medicines in a multimodal strategy. A high level of total or partial level of agreement was reached in several issues: greater than 99 % agreement was reached regarding the fact that opioids are highly effective and safe drugs, health professionals must be well trained in their management (97 %), these medicines must be accessible to all patients who require it when the doctor deems it necessary (94 %) and that they are indispensable in the treatment of pain severe (93 %). The lowest degree of agreement was observed regarding the idea of a single prescriber (total agreement 50 % and partial agreement 34 %), that respiratory depression-tolerance-addiction are rare and should not be a barrier to their clinical use (51 % total agreement, 33 % partial agreement, 16 % do not agree) or that its use does not affect the life expectancy of the patient.

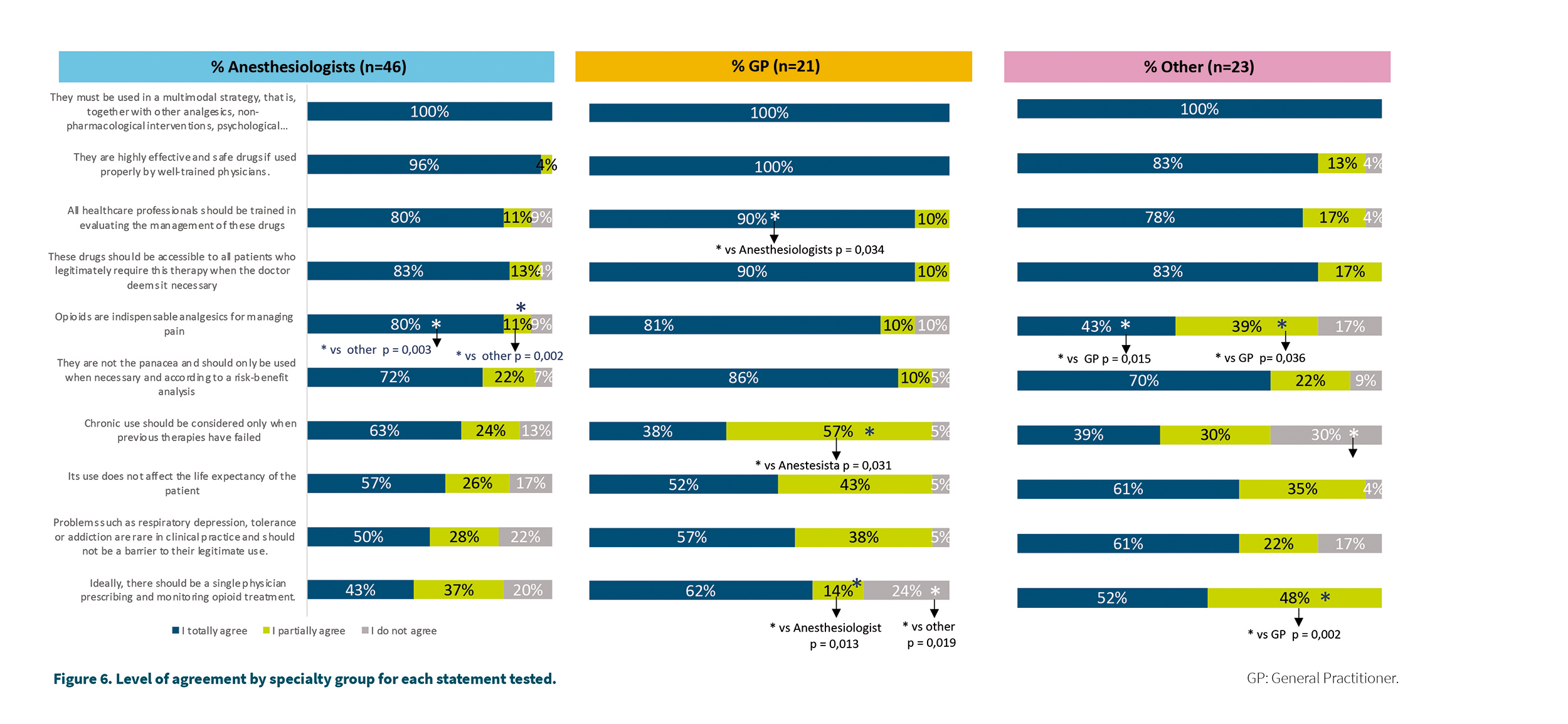

When comparing the levels of agreement between the specialty groups, some significant differences were found:

– 43 % of the “Other specialties” group totally agreed that opioids are not the panacea and should only be used when necessary, 39 % partially agreed with this statement, these figures being significantly lower than those observed in the GP group (81 %, p = 0.015 and 10 %, p = 0.036, respectively) or Anesthesia (80 %, p = 0.003 and 11 %, p = 0.002, respectively).

– 90 % of the physicians in the GP group fully agreed that opioid drugs should be accessible to all patients who legitimately require this therapy, this figure being significantly higher than that observed in the group of Anesthesiologists (80 %, p = 0.034).

Figure 6 shows the detail of these levels of agreement by specialty group, as well as the corresponding significant differences.

Discussion

Both the recommendations of the EFP (2) and those of SEMDOR (1) are fundamental tools when it comes to guiding the clinical practice of health professionals involved in the management of this type of medicine. But it is essential to ensure that these recommendations are accepted and followed in clinical reality or else they will not be effective. The objective of this work has been precisely to try to quantify the level of agreement that the members of SEMDOR have with the recommendations worked with the experts of the society so that they can on the one hand anticipate the implementation in clinical practice and on the other hand, know those recommendations that must be adapted or adjusted in future editions of the guidelines. The level of agreement that opioid medicines are relevant in the treatment of moderate-intense pain has been very high, especially among primary care physicians, who are responsible for 74 % of prescriptions for these drugs in our country (3).

With respect to the recommendations tested in the study, we can say that all reached a level of total or partial agreement greater than 80 %. One of the recommendations with a lower agreement was that there must be a single doctor to prescribe and monitor the patient in treatment with opioids (50 % in total agreement, 34 % in partial agreement and 16 % in disagreement). Although the origin of this recommendation is based on the need to have greater control over the different opioids and treatments that a pluri-pathological patient may be receiving, it is also logical that in certain circumstances a single prescriber may be no implementable at the level of clinical practice. This recommendation might be less necessary to the extent that medical information systems are integrated so that all physicians treating a patient can access all medication and treatments prescribed by other physicians. In fact, in this study it is the group de anesthesiologists the ones who least agree with the single prescriber recommendation, understanding that it would be unfeasible for them to function without the prescriptions and monitoring carried out in primary care. It seems logical, therefore, to modulate this recommendation towards one that implies that the prescribing physician of opioids should have access to the medication prescribed by any other physician.

Another statement in which the level of agreement was lower than the rest is related to the fact that respiratory depression or addiction are rare in clinical practice and should not be a barrier to legitimate use (51 % totally agree, 33 % somewhat agree, 16 % disagree). The level of agreement was higher in the group of anesthesiologists (63 % agreement, 24 % partial agreement and 13 % do not agree) and lower in the rest of specialists (39 %, 30 % and 30 %, respectively) while it was intermediate in primary care (38 %, 57 % and 5 %, respectively). In this case, it may be necessary to specify what the legitimate use of an opioid drug implies, as well as to insist on medical education to differentiate abuse, tolerance and addiction as very different clinical entities (4).

The results regarding the level of agreement with the statement that the use of opioid medicines does not affect the life expectancy of the patient are surprising (54 % totally agree, 29 % somewhat agree and 17 % do not agree). It seems necessary to explain and influence the fact that the use of these drugs does not affect the life expectancy of patients.

Regarding the importance of these drugs to treat intense pain, 74 % agree that they are indispensable, 19 % agree somewhat and 9 % do not agree with its indispensability, with the primary care group showing the highest level of agreement (86 %, 10 % and 5 %, respectively). Therefore, a high percentage of participants consider that these drugs are indispensable in this type of pain, always understanding their use within a multimodal strategy. In fact, the statement that reaches 100 % total agreement is precisely the one that indicates that opioid medicines should be used in a multimodal strategy, along with other analgesics, non-pharmacological interventions, psychological support and rehabilitation. Likewise, they are considered highly effective and safe drugs if used properly by trained doctors (93 % total agreement, 6 % partial agreement, 1 % do not agree). Primary care physicians are the ones who showed the highest level of agreement with this statement (100 % totally agree) followed by anesthesiologists (96 % totally agree, 4 % partially agree).

Considering all the results we can affirm that a large majority of SEMDOR members consider opioid medicines to be highly effective if used properly, as part of a multimodal strategy and are indispensable for the control of severe pain. These medicines must be accessible to all patients who require them according to the doctor’s criteria and that a risk-benefit analysis is necessary to determine their usefulness.

The control system of prescription and dispensing of opioid medicines in Spain, as well as the structure of the health system itself in our country have acted, among many other factors (5), as differentiating and protective elements with respect to the threat of epidemic that other countries such as the United States or Canada have suffered. The different levels of care, the system of control of prescription and dispensing (prescription of narcotics) have been essential and we must continue to reinforce them with recommendations that allow us to achieve the optimal balance between the control of its use and the control of pain. The lack of control is as harmful as the excess of limitations when prescribing these medicines. Medical training and education are an essential means of avoiding these distortions and is one of the main functions of any scientific society at the level. The APPEAL study (6) showed that there was a lack of training on pain and its treatment by showing that, among 242 Medical Schools in 15 EU countries, 82 % did not have courses dedicated to pain.

In order to compare these recommendations with others previously made in Spain, several guides or documents on the safe use of opioids were analyzed, either by scientific societies or in various reports of the Ministry of Health, Social Services and Equality in 2015 and 2017, the latter elaborated in consensus with some scientific societies (7-12). In these documents there are a series of shortcomings that have been tried to fill in this work. The 2015 document focuses attention on the clinical management of drugs even making a specific section for each molecule, but they do not talk about public health measures or the necessary changes in systematics and coordination or training programs for prescribers and dispensers.

Special mention deserves the consensus guide of 2017, which is the most extensive, where I have found several errors of analysis and diagnosis of the situation in Spain. With regard to the SED documents, they are too general and not very specific in terms of the measures to be taken. In none of these cases was a subsequent survey carried out to assess the degree of agreement of health professionals with these documents or recommendations. As far as we have been able to find out, this is the first work that quantitatively evaluates the degree of agreement with opioid recommendation guidelines in our country. It is clear that the drafting of recommendations and guidelines are ineffective if they are not properly implemented in actual clinical practice. In the United States there has been no lack of multiple guidelines or recommendations (13-19) on the use of opioid drugs (some of them seeking the limitation of use rather than proper use) and yet the effectiveness of their implementation has been very limited.

The first step to bring the SEMDOR recommendations (1) closer to real clinical practice has been to carry out this survey to identify the aspects that need to be improved both at the level of recommendations and at the level of medical education.

As the main limitation of this work, we must mention that the response rate was low (15 %) with respect to the universe invited to participate although being a finite sample the sampling error is in an acceptable range of less than 10%. Given the multidisciplinarity of SEMDOR’s members, the survey has been answered by doctors of various medical-health profiles, although the majority of the participants were anesthesiologists or primary care physicians who together have represented 84% of the total.

Conclusions

First of all, it should be noted that medical education, as well as the implementation of clinical practice recommendations, allow us to achieve an optimal balance between prescription control and adequate pain control. It is important to know the levels according to the recommendations, as well as to identify points where further medical training regarding opioid use may be necessary. This work shows that opioids are very relevant medicines in the management of moderate-intense pain. Regarding the general statements and recommendations, there has been a level of agreement greater than 90% in the following aspects: the use of these drugs in a multimodal strategy, these are highly effective and safe drugs, the need for health professionals to be well trained in their management, the need to be accessible to all patients who require it according to medical criteria. Therefore, we can conclude that the doctors who use these medicines must have a good training in the management and that these drugs must be accessible to patients in whom the doctor considers them necessary for the treatment of pain.

Annex 1. Cuestionario utilizado.

Este cuestionario se refiere a los fármacos opioides usados actualmente en la práctica clínica de España. Entendemos por opioides potentes cualquier formulación de: morfina, fentanilo oxicodona, tapentadol, hidromorfona y buprenorfina.

Conteste las preguntas en base a su opinión y experiencia clínica.

BIBLIOGRAFÍA

1. Regueras E, Torres LM, Velazquez I. Spanish Multidisciplinary Society of Pain (SEMDOR) clinical practice recommendations for the good medical use of prescription opioids in the treatment of chronic non-oncology pain. MPJ. 2022;2:27-51. DOI: 10.20986/mpj.2022.1024/2022.

2. O’Brien T, Christrup LL, Drewes AM, Fallon MT, Kress HG, McQuay HJ, et al. Position paper on appropriate opioid use in chronic pain management. Eur J Pain. 2017;21(1):3-19. DOI: 10.1002/ejp.970.

3. Regueras E, López-Guzmán J. Prescripciones de opioides en España entre 2019 y 2020: qué especialidades médicas lo están prescribiendo y en qué indicaciones. MPJ. 2021;1:5-12.

4. Definitions Related to the Use of Opioids for the Treatment of Pain: Consensus Statement of The American Academy of Pain Medicine, the American Pain Society, and the American Society of Addiction Medicine. 2001 American Academy of Pain Medicine, American Pain Society and American Society of Addiction Medicine.

5. Regueras E, López-Guzmán J. ¿Qué podemos aprender de los errores en el abordaje de la crisis opioides en Estados Unidos?. Rev OFIL·ILAPHAR. 2022;32(2):197-202.

DOI: 10.4321/S1699-714X20220002000013.

6. Briggs EV, Battelli D, Gordon D, Kopf A, Ribeiro S, Puig MM, et al. Current pain education within undergraduate medical studies across Europe: Advancing the Provision of Pain Education and Learning (APPEAL) study. BMJ Open. 2015 Aug 10;5(8):e006984. DOI: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006984.

7. Jara C, Del Barco S, Grávalos C, Hoyos S, Hernández B, Muñoz M, et al. SEOM clinical guideline for treatment of cancer pain (2017). Clin Transl Oncol. 2018;20(1):97-107.

8. Grupo de trabajo de Opioides. Sociedad Española de Dolor. Decálogo en el manejo de opioides [Internet]. Sociedad Española del Dolor; 12 de marzo de 2018 [Accedido el 10 de abril 2021]. Disponible en https://www.sedolor.es/download/decalogo-correcto-manejo-opioides/

9. Grupo de trabajo de Opioides. Sociedad Española de Dolor. Conclusiones de la jornada del Grupo de Opioides [Internet]. Sociedad Española del Dolor; 10 de marzo de 2018 [Accedido de 10 abril de 2021]. Disponible en: https://www.sedolor.es/download/conclusiones-la-jornada-del-grupo-opioides-madrid-10-marzo-2018/

10. Álvarez Mazariegos JA, Calvete Waldomar S, Fernández-Marcote Sánchez-Mayoral RM, Guardia Serecigni J, Henche Ruiz AI, et al. Guía consenso sobre el buen uso de analgésicos opioides. Gestión de riesgos y beneficios. Valencia: SEMFyC, FAECAP, SECPAL; junio de 2017 Disponible en: https://pnsd.sanidad.gob.es/profesionales/publicaciones/catalogo/bibliotecaDigital/publicaciones/pdf/2017_GUIA_Buen_uso_opioides_Socidrigalcohol.pdf

11. Prácticas seguras para el uso de opioides en pacientes con dolor crónico. Informe 2015. Documento de consenso sobre prácticas para el manejo seguro de opioides en pacientes con dolor crónico. Madrid: Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad; 2015. Disponible en: https://www.mscbs.gob.es/gl/biblioPublic/publicaciones.do?metodo=detallePublicacion&publicacion=16593

12. Guidelines for the Use of Controlled Substances in the Treatment of Pain [Internet]. New Hampshire Medical Society; 1998. Disponible en: https://www.nhms.org/sites/default/files/Pdfs/NH%20Pain%20Management%20Guidelines.pdf

13. The Joint Commission. Facts About Joint Commission Accreditation Stan- dards for Healthcare Organizations: Pain Assessment and Management [Internet]. 2018; Disponible en: https://www.jointcommission.org/facts_about_joint_commis- sion_accreditation_standards_for_health_care_organizations_pain_assess- ment_and_management/

14. Jones MR, Viswanath O, Peck J, AD Kaye, Gill JS, Simopoulos TT. A brief his- tory of the opioid epidemic and strategies for pain medicine. Pain Ther. 2018;7(1):13-21. DOI: 10.1007/s40122-018-0097-6.

15. Phillips DM. Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO) Pain Management Standards Are Unveiled. JAMA. 2000;284(4):428-9.

DOI: 10.1001/jama.284.4.423b.

16. Abuse-Deterrent Opioid Analgesics [Internet]. Food and Drug Administration; 2019. Disponible en: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/postmarket-drug-safety-information-patients-and-providers/abuse-deterrent-opioid-analgesics

17. National Drug Control Strategy [Internet]. 2011; Disponible en: https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/ondcp/ndcs2011.pdf

18. Comprehensive addiction and recovery act of 2016 [Internet]. America CUSo. con- gress.gov. 2019; Disponible en: https://www.congress.gov/bill/114th-congress/senate-bill/524