Introduction

In 2020, the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) redefined pain as “an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated, or similar to that associated, with actual or potential tissue damage” (1). In addition, the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11) characterizes chronic pain as pain that persists or recurs for more than three months (2). These definitions highlight the complexity and variability of pain in terms of symptomatic presentation, not only as a physical sensation, but as a multidimensional phenomenon that profoundly impacts the quality of life of patients.

Pain affects billions of people worldwide on a daily basis, constituting not only a universal experience, but also one of the main causes of disability and mortality (3). Its omnipresence and its implications for quality of life and social well-being make it an unavoidable priority for global health. Within this scenario, neuropathic pain, a subtype of chronic pain, emerges as a particularly complex clinical challenge. Its high prevalence, affecting 7-10 % of the general population, and its resistance to conventional analgesic treatments and other pharmacological approaches such as antidepressant and antiepileptic drugs, underscore the need for more effective and personalized therapies. This subtype of pain, often refractory, not only perpetuates patient suffering, but also overburdens healthcare systems worldwide (4).

In this context, TMS has emerged as a promising tool in the management of chronic pain. TMS is a non-invasive neuromodulation technique that uses electromagnetic pulses directed to specific areas of the brain to modulate neuronal activity (5,6). Since its introduction into neuroscience as a tool to investigate brain processes (7), through its diagnostic use, TMS, particularly in its repetitive version (rTMS), has also been shown to be effective in a variety of conditions, including depressive disorders (8), neurological rehabilitation (9) and, more recently, in the treatment of chronic pain (10).

Among the available non-invasive neuromodulation modalities, TMS is distinguished by its ability to intervene in a focal and controlled manner in specific brain regions, with a favorable safety profile and without the risks associated with more invasive interventions and with a higher potential risk of developing seizures (6). This technique joins a growing therapeutic arsenal that includes other modalities such as direct current stimulation (tDCS) and electrical stimulation (noninvasive or percutaneous) of the vagus nerve (tVNS), each with its own applications and limitations. However, TMS stands out particularly in the field of chronic pain because of its personalization capability and its direct impact on neural circuits of the “pain neuromatrix” (11).

The present article aims to explore the state of the art in the use of TMS for chronic pain management, focusing on its rationale, efficacy and therapeutic algorithms. Through an exhaustive review of the literature and the experience of pioneers such as Dr. Jean-Pascal Lefaucheur, we seek to outline a comprehensive framework to optimize the indications and results of this tool in clinical practice and to propose an algorithm for its practical and logical use in the area of chronic pain.

Non-invasive neuromodulation in pain

Chronic pain, particularly neuropathic pain, represents a significant challenge in clinical practice. Noninvasive neuromodulation techniques have emerged as promising alternatives by offering effective therapeutic options without the risks associated with invasive procedures. Among these, transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) has shown usefulness in certain types of pain, although its effects tend to be of short duration and highly variable among patients (12). On the other hand, transcutaneous vagus nerve electrical stimulation (tVNS) offers an innovative approach, although its clinical application in pain is still at an incipient stage (13).

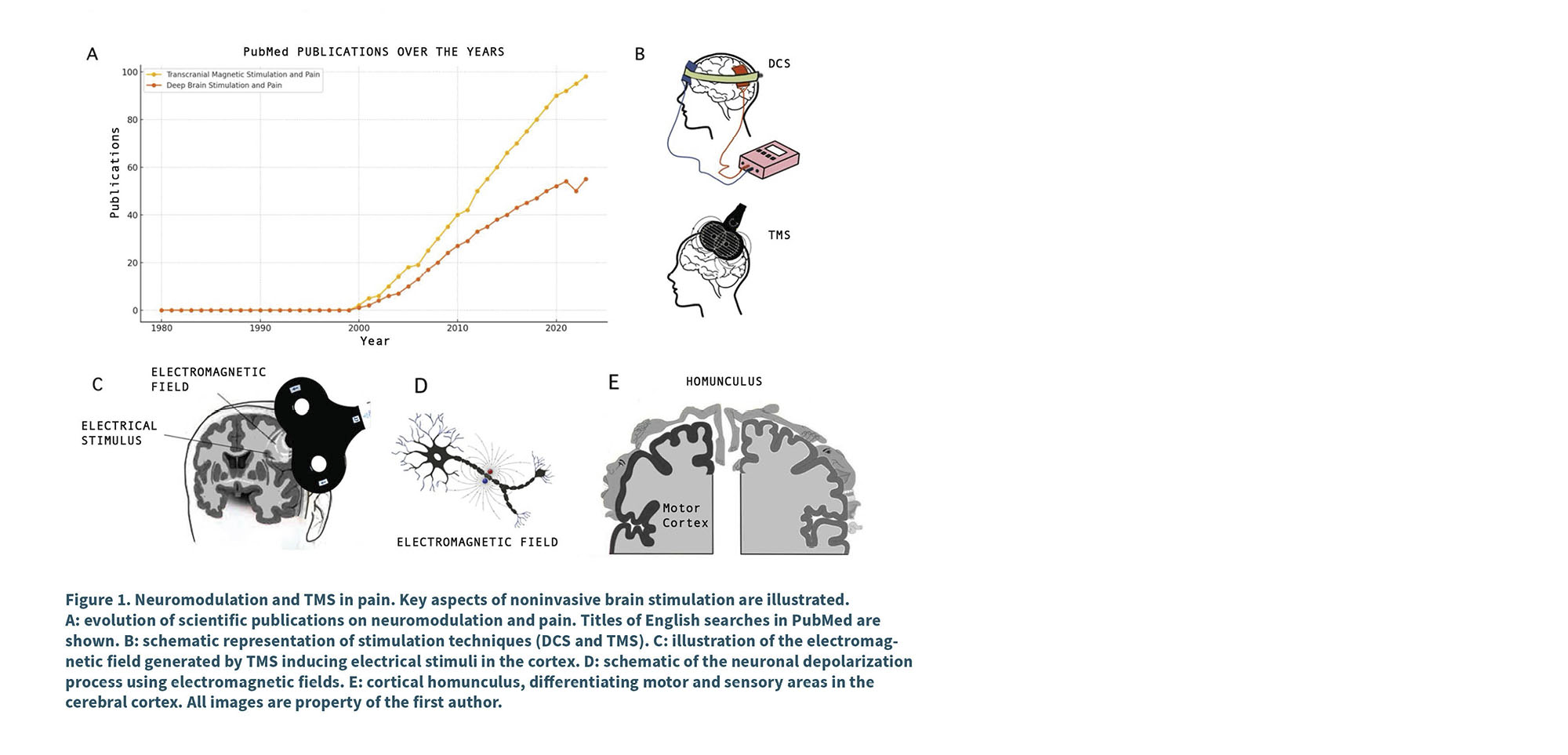

Within this scenario, TMS has gained a prominent place due to its ability to precisely intervene in brain regions involved in pain perception. Its safety profile, supported by growing scientific evidence, and the possibility of personalizing treatment parameters, have consolidated TMS as a key tool in the management of several variants of chronic pain (14). In recent years, its use has grown steadily, positioning it as a highly relevant therapeutic option for patients with insufficient response to traditional treatments (Figure 1 A and B).

TMS pain

The basis of this technique lies in the generation of electro-magnetic pulses by means of an external device placed on the scalp. These induce electrical currents in the underlying cerebral cortex, modulating neuronal activity in a non-invasive manner (15). Depending on the frequency and intensity used, stimulation can cause membrane depolarization and increase or decrease cortical neuronal excitability, facilitating changes in different circuits (16). (Figure 1 C and D).

Several neurophysiological theories approach to explain why rTMS treatment effectively relieves pain. To summarize some briefly, and taking into account that the action occurs through multiple synergistic mechanisms such as modulation of cortical excitability and synaptic reorganization, especially when stimulating the primary motor cortex (M1) with high frequencies, a long-term potentiation (LTP) is observed, a phenomenon of synaptic plasticity that is defined as a lasting increase in the strength of the connections between neurons (17). On the other hand, it has been described that it inhibits ascending nociceptive pathways through cortico-thalamic projections, thus reducing pain perception (18). Other lines of research point to the release of endogenous opioids, reinforcing the internal analgesic mechanisms of the central nervous system (19), decreased neuroinflammation with reduced gliosis, proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-1β, increased anti-inflammatory factors such as IL-10 (20), and improved functional connectivity between structures such as the cortex, thalamus and hypothalamus, activating the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, contributing to a less pain-sensitive neurophysiological environment (21).

Probably, the analgesic effect observed is not due to a single isolated mechanism, but to the convergence of several of these processes acting in parallel, which together configure a brain environment more resistant to the perception of pain in its various characteristics.

Primary motor cortex stimulation for chronic pain: basics

In this context, TMS has been the subject of numerous studies investigating its efficacy in the treatment of chronic pain, focusing particularly on the stimulation of M1 both in the cortical region corresponding to the painful area and in the cortex corresponding to the upper limb, due to its wider extension in the motor homunculus (Figure 1 E). Several investigations have explored the mechanisms by which M1 stimulation may influence pain perception.

Among them, a key study by Peyron et al. in 2007 investigated the brain mechanisms underlying the analgesic effects of stimulation by electrode implantation in M1 using positron emission tomography (PET) (17). The results show significant changes in cerebral blood flow at two times, namely, intra-stimulation and post-stimulation. The cortical and subcortical regions associated with pain control that showed changes in cerebral blood flow were the pregenual anterior cingulate cortex, thalamus and midbrain, including the periaqueductal gray matter.

In relation to the times at which it was measured, during stimulation, activation was observed in the medial cingulate cortex, while in the post-stimulation period, broader networks including prefrontal areas, orbitofrontal and subcortical structures were activated. This pattern suggests that TMS applied on M1 may act through complex descending mechanisms, which modulate nociceptive transmission through connections between cortex, basal nuclei and other brainstem regions at different times beyond the time of stimulation.

These findings highlight the central role of the primary motor cortex as a therapeutic target in the management of chronic pain.

Clinical indications and consensus on the use of TMS for the treatment of pain

In 2004 Jean-Pascal Lefaucheur and co-workers reported the pioneering case of a woman with peripheral neuropathic pain resistant to pharmacological therapy who was able to obtain control of her pain for more than a year by performing a monthly TMS session, until the placement of a cortical neurostimulator. The initial average visual numeric scale values were greater than 7/10. After each session, the average numeric visual scale was always less than 5.5/10 (22).

In the year 2025, we already have international consensus clinical guidelines on the use of rTMS for multiple pathologies (1,23), there is level of evidence “A” for the use of high frequency rTMS on the primary motor cortex (M1) in the treatment of post-stroke central neuropathic pain, trigeminal neuralgia and pain associated with spinal cord injury. Controlled clinical studies have shown significant reductions in pain intensity; for example, in patients with postherpetic neuralgia, relief reached 45-50 %, with sustained effects up to three months after treatment (24). In cases of cancer-related pain, reductions of 35-40% were observed, although with a more transient effect (25).

In addition, recent research highlights that the use of neuronavigation-guided rTMS can optimize the analgesic effect, and that even using a universal target such as the motor area of the hand achieves favorable responses in multiple types of pain, regardless of location. A positive cumulative effect has also been reported with sustained repetition of sessions over time, especially in post-stroke and facial central pain (26,27).

Additional efficacy has been observed in conditions such as fibromyalgia , where rTMS has shown both analgesic and functional benefits in several clinical trials (28).

Additionally, in the latest Latin American and Caribbean consensus on noninvasive central nervous system neuromodulation for chronic pain management published in Pain Reports, which provides evidence-based recommendations, highlights that M1 stimulation using high-frequency TMS has a level A recommendation for fibromyalgia and neuropathic pain, and a level B for myofascial or musculoskeletal pain, complex regional pain syndrome, and migraine. These recommendations are based on a systematic review of clinical studies demonstrating the efficacy of TMS and various other therapeutic strategies in the treatment of pain (29).

Protocolization of TMS in neuropathic and chronic pain

Chronic cortical stimulation and TMS

As mentioned above, TMS treatment of the primary motor cortex is closely related to the treatment of chronic cortical stimulation of M1 (CSM) initially proposed by Tsubokawa and Meyerson (30,31). This technique involves epidural implantation in the area corresponding to the pre-central gyrus, identified intraoperatively. This electrode is connected by means of extensions to an impulse generator, which is implanted in a subcutaneous pocket below the clavicle, and is responsible for the administration of electrical stimuli whose parameters can be externally modified by telemetry to obtain the best “tailor-made” programming for each particular patient.

This therapeutic approach has shown efficacy in relieving refractory neuropathic pain and motor function in certain movement disorders. In 2019 Henssen et al. published an article that provides a systematic analysis and predictive model through neural networks that identifies point variables associated with improved response to M1 MCS implantation in patients with chronic pain (32).

The model used was a multilayer artificial neural network (ANN), which allows the identification of complex correlations between multiple clinical and demographic variables. Henssen et al. evaluated more than 358 patients and found six variables with significant predictive value:

1. Patient sex. Women responded better to treatment.

2. Origin of the lesion. Central lesions showed a higher response rate than peripheral lesions.

3. Preoperative NRS pain scale. A lower preoperative score was associated with better outcomes.

4. Preoperative use of rTMS. Patients who responded positively to prior TMS had a higher likelihood of success with MCS.

5. Preoperative opioid use. It was associated with worse outcomes.

6. Follow-up period. Longer follow-up showed better clinical response rates.

The use of repetitive TMS as a predictive tool prior to CSM implantation is one of the key findings of the article, highlighting its relevance not only as a treatment, but also as a prognostic assay. This practice allows assessment of the patient’s potential response prior to an invasive procedure, optimizing candidate selection for CSM therapy and suggests a more personalized approach to candidate selection, optimizing therapy success rates.

Predictors and algorithms used in the treatment of pain with TMS

Similar work to that of Henssen was more recently published looking for predictors of response to high-frequency stimulation by TMS over M1. In a study published earlier this year (33), the investigators employed an experimental design involving high-frequency rTMS application over M1 in patients with neuropathic pain. Various clinical and demographic variables of the participants were assessed prior to treatment. Subsequently, treatment responses were analyzed to identify patterns and correlations between patients’ baseline characteristics and rTMS efficacy.

From this methodology they arrived at a predictive algorithm that included three main variables: two psychological (depressive symptoms and the magnification dimension of the Pain Catastrophizing Scale) and one related to pain distribution (distal lower extremity pain). This model demonstrated a sensitivity of 85 % (p = 0.005) and a specificity of 84 % (p < 0.0001) for predicting a good response to rTMS treatment in M1 at 25 weeks.

In this context, the work of the previously mentioned physician and researcher, Jean-Pascal Lefaucheur is once again fundamental as a key reference in the protocolization and standardization of the technique. His work has not only driven clinical implementation, but has also laid the foundations for evidence-based practice.

In reviewing his extensive literature on the subject, an article entitled “A Practical Algorithm for Using rTMS to Treat Patients with Chronic Pain” (34), where Lefaucheur presents a structured framework for the implementation of rTMS in patients with chronic pain, is particularly striking. In this article, he highlights the importance of parameters such as stimulation frequency, intensity and anatomical precision. A central aspect of this publication is the ability to visually summarize patient management in a therapeutic algorithm.

“TMS pain-roadmap”

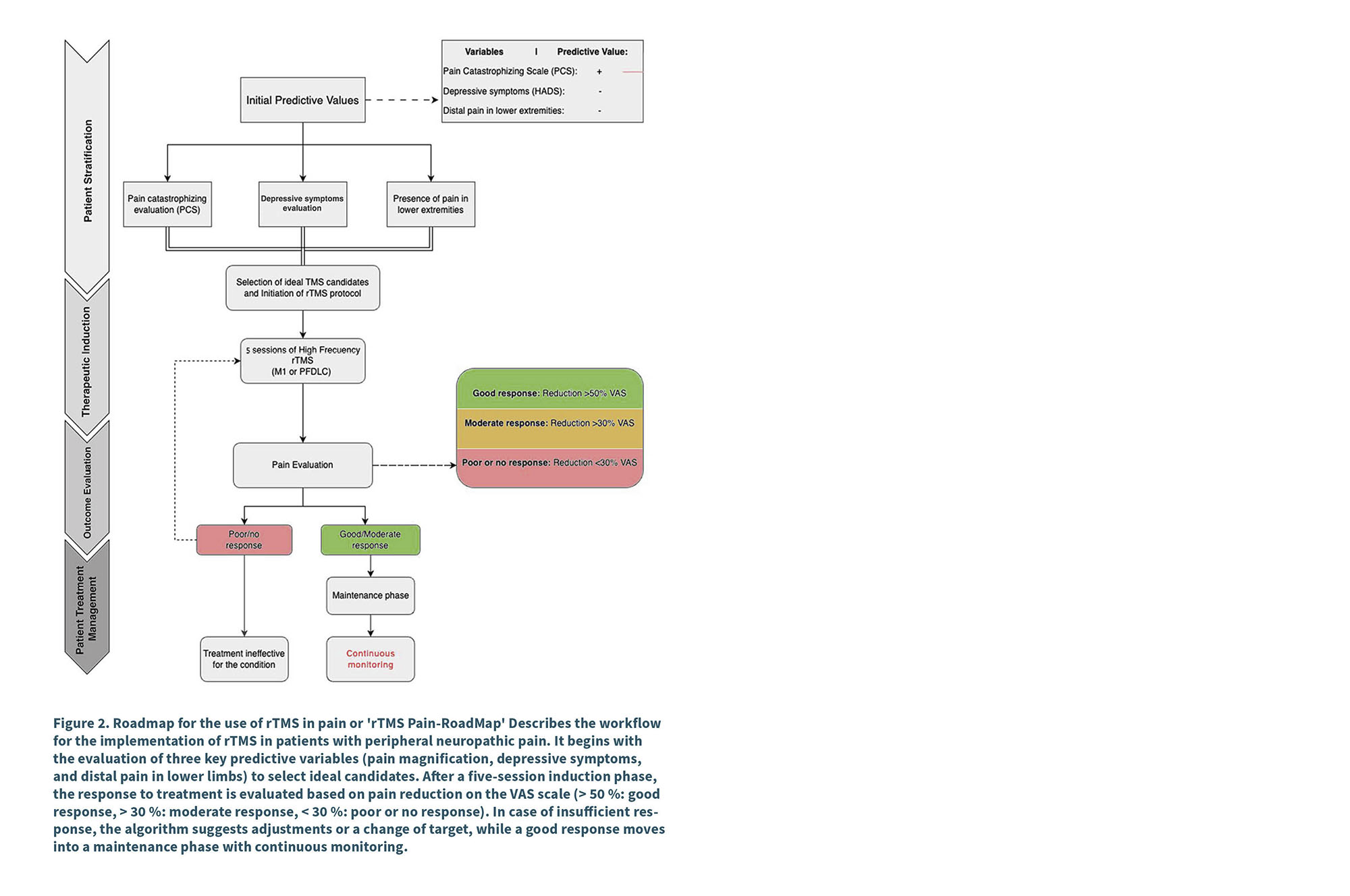

A Based on the advances described in the previous chapter, and considering the most recent findings on the prediction of response to rTMS treatment in M1, we have developed a clinical algorithm, using the clinical predictors and the therapeutic algorithm named in the previous chapter (33,34). Combining these approaches forms a practical, Spanish-language framework for approaching TMS therapeutics in a patient with chronic pain. This algorithm, depicted in Figure 2, integrates key variables such as pain magnification (PCS), depressive symptoms (HADS), and lower extremity pain location, which have been shown to be robust predictors for optimizing patient selection (33).

The flow begins with the assessment of these initial predictor variables, followed by careful selection of ideal candidates for treatment. Subsequently, an induction phase is implemented with a standard five-session rTMS protocol, whose response is evaluated according to pain reduction on the VAS scale (> 50 % for good response, > 30 % for moderate response). In cases of insufficient response, the algorithm contemplates adjustments in the parameters or changes in the stimulation target, optimizing the interventions before considering the treatment as ineffective. For those who achieve a good response, a maintenance phase with continuous monitoring is established.

This model not only integrates the most relevant evidence, but also proposes a practical tool to guide clinical decision making in the treatment of neuropathic pain with rTMS.

Conclusion

That Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation has emerged as a transformative tool in the management of various pathologies, including chronic pain, providing a viable and non-invasive alternative to traditional therapies is a fact. Through its ability to focalize neuronal activity, this technique opens a new path towards therapeutic personalization. With the leadership of pioneers like Dr. Jean-Pascal Lefaucheur and the development of practical clinical algorithms, significant progress has been made in the protocolization of this therapy, optimizing both patient selection and treatment parameters. This progress, supported by increasingly robust evidence and new predictive methodologies, not only improves clinical outcomes but also helps avoid costly and ineffective treatments for patients less likely to respond.

The challenge now is to integrate these tools into daily clinical practice in an accessible, efficient and universal manner.

In the words of the great humanist physician Edward Trudeau, “Cure sometimes, relieve often, console always”. The practice of tirelessly seeking new tools for the treatment of pain embodies this philosophy.

Acknowledgments

We especially thank Dr. Eduardo Marchevsky, an expert in pain medicine, for his valuable contributions to the editing and supervision of this work.

Conflict of interest

None.

Funding

None.

references

1. Raja SN, Carr DB, Cohen M, Finnerup NB, Flor H, Gibson S, et al. The revised International Association for the Study of Pain definition of pain: Concepts, challenges, and compromises. Pain. 2020;161(9):1976-82. DOI: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001939.

2. World Health Organization. ICD-11 for Mortality and Morbidity Statistics (ICD-11 MMS). Disponible en: https://icd.who.int.

3. Zajacova A, Grol-Prokopczyk H, Zimmer Z. Pain prevalence across 52 countries: new empirical evidence and trends from 1991 to 2015. J Pain. 2022;23(3):446-56.

4. Treede RD, Jensen TS, Campbell JN, Cruccu G, Dostrovsky JO, Griffin JW, et al. Neuropathic pain: Redefinition and a grading system for clinical and research purposes. Neurology. 2008;70(18):1630-5. DOI: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000282763.29778.59.

5. Malavera MA, Fregni F, Carrillo-Ruiz JD, Sánchez-Loyo LM, Alonso-Vanegas MA, Alonzo J, et al. Fundamentos y aplicaciones clínicas de la estimulación magnética transcraneal en neuropsiquiatría. Rev Colomb Psiquiatr. 2014;43(3):146-57. DOI: 10.1016/S0034-7450(14)70040-X.

6. Edwards MJ, Talelli P, Rothwell JC. Transcranial magnetic stimulation for the neurological patient: Scientific principles and applications. Pract Neurol. 2008;8(6):343-9.

7. Kobayashi M, Pascual-Leone A. Transcranial magnetic stimulation in neurology. Lancet Neurol. 2003;2(3):145-56. DOI: 10.1016/S1474-4422(03)00321-1.

8. Rizvi SJ, Khan A. Use of transcranial magnetic stimulation for depression. Cureus. 2019;11(5):e4736. DOI: 10.7759/cureus.4736.

9. Lefaucheur JP, Drouot X, von Raison F, Ménard-Lefaucheur I, Cesaro P, Nguyen JP. Usefulness of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in the treatment of motor symptoms of stroke. Neurophysiol Clin. 2012;42(5-6):281-8.

10. Fitzgibbon BM, Pellizzer G, Sforza A, Fogassi L, Cossu G. New updates on transcranial magnetic stimulation in chronic pain. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2022;26(5):355-66.

11. Xiong HY, Yang Y, Zhang Q, Li Y, Fan J. Non-invasive brain stimulation for chronic pain: State of the art and future directions. Front Mol Neurosci. 2022;15:888716. DOI: 10.3389/fnmol.2022.888716.

12. Vergallito A, Feroldi S, Pisoni A, Romero Lauro LJ. Inter-individual variability in tDCS effects: A narrative review on the contribution of stable, variable, and contextual factors. Brain Sci. 2022;12(5):522. DOI: 10.3390/brainsci12050522.

13. Costa V, Gianlorenço A, Andrade MF, Camargo L, Menacho M, Arias Avila M, et al. Transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation effects on chronic pain: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain Rep. 2024;9(5):e1171. DOI: 10.1097/PR9.0000000000001171.

14. Lefaucheur JP, Aleman A, Baeken C, Benninger DH, Brunelin J, di Lazzaro V, et al. Evidence-based guidelines on the therapeutic use of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS): An update (2014-2018). Clin Neurophysiol. 2020;131(2):474-528. DOI: 10.1016/j.clinph.2019.11.002.

15. Chervyakov AV, Chernyavsky AY, Sinitsyn DO, Piradov MA. Possible mechanisms underlying the therapeutic effects of transcranial magnetic stimulation. Front Hum Neurosci. 2015;9:303. DOI: 10.3389/fnhum.2015.00303.

16. Yang S, Chang MC. Effect of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation on pain management: a systematic narrative review. Front Neurol. 2020;11:114. DOI: 10.3389/fneur.2020.00114.

17. Peyron R, Faillenot I, Mertens P, Laurent B, Garcia-Larrea L. Motor cortex stimulation in neuropathic pain: Correlations between analgesic effect and hemodynamic changes in the brain. A PET study. Neuroimage. 2007;34(1):310-21. DOI: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.08.037.

18. Garcia-Larrea L, Peyron R, Mertens P, Grégoire MC, Lavenne F, le Bars D, et al. Electrical stimulation of motor cortex for pain control: A combined PET-scan and electrophysiological study. Pain. 1999;83(2):259-73. DOI: 10.1016/S0304-3959(99)00114-1.

19. Taylor JJ, Borckardt JJ, George MS. Endogenous opioids mediate left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex rTMS-induced analgesia. Pain. 2013;154(11):2133-41.

20. Liu J, Wang Y, Lin Y, Zhang J, Cao X, Wang J, et al. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation inhibits microglial activation and alleviates chronic neuropathic pain in rats. J Pain Res. 2018;11:2941-52.

21. Sun Y, Li N, Liu X, Chen Y, Yuan X, Li F, et al. rTMS improves functional connectivity and reduces neuroinflammation in spinal cord injury-induced neuropathic pain. Neurobiol Dis. 2023;181:105918.

22. Lefaucheur JP, Drouot X, Nguyen JP. Neurogenic pain relief by repetitive transcranial magnetic cortical stimulation depends on the origin and the site of pain. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004;75(4):612-6. DOI: 10.1136/jnnp.2003.022236.

23. Lefaucheur JP, Drouot X, Ménard-Lefaucheur I, Keravel Y, Nguyen JP. Evidence-based guidelines on the therapeutic use of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation: 2014 update. Clin Neurophysiol. 2014;125(11):2150-206. DOI: 10.1016/j.clinph.2014.05.021.

24. Ma SM, Ni JX, Li XY, Wang TJ, Guo Y, Chen HS, et al. High-frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation reduces pain in postherpetic neuralgia. Pain Med. 2015;16(11):2162-70. DOI: 10.1111/pme.12832.

25. Khedr EM, Kotb HI, Mostafa MG, Ahmed MA, Sadek R, Rothwell JC. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in neuropathic pain secondary to malignancy: A randomized clinical trial. Eur J Pain. 2015;19(4):519-27. DOI: 10.1002/ejp.576.

26. Pommier B, Créach C, Beauvieux V, Nuti C, Vassal F, Peyron R. Robot-guided neuronavigated rTMS as an alternative therapy for central (neuropathic) pain: Clinical experience and long-term follow-up. Eur J Pain. 2016;20(6):907-16. DOI: 10.1002/ejp.815.

27. Quesada C, Attal N, Gautron M, Brasseur L, Baudic S, et al. Robot-guided neuronavigated repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) in central neuropathic pain. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2018;99(11):2203-15.e1. DOI: 10.1016/j.apmr.2018.04.013.

28. Boyer L, Pinsard B, Chupin M, Dousset A, et al. Effects of unilateral repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation of the motor cortex on chronic widespread pain in fibromyalgia. Neurophysiol Clin. 2014;44(3):261-7.

29. Baptista AF, Fernandes AMBL, Nunes Sa K, Hideki Okano A, Russowsky Brunoni A, Lara-Solares A, et al. Latin American and Caribbean consensus on noninvasive central nervous system neuromodulation for chronic pain management (LAC2-NIN-CP). Pain Rep. 2019;4(1):e692. DOI: 10.1097/PR9.0000000000000692.

30. Hsieh JC, Meyerson BA, Ingvar M. Electric precentral gyrus stimulation alleviates the pain of trigeminal neuropathy: A PET study of central processing of chronic pain. Neuroimage. 1996;3(3, Suppl):S489.

31. Tsubokawa T, Katayama Y, Yamamoto T, Hirayama T, Koyama S. Chronic motor cortex stimulation in patients with thalamic pain. J Neurosurg. 1993;78(3):393-401. DOI: 10.3171/jns.1993.78.3.0393.

32. Henssen DJ, Witkam RL, Dao J, Comes DJ, van Cappellen van Walsum AM, Kozicz T, et al. Systematic review and neural network analysis to define predictive variables in implantable motor cortex stimulation to treat chronic intractable pain. J Pain. 2019;20(9):1015-26. d DOI: 10.1016/j.jpain.2019.02.004.

33. Attal N, Quesada C, Gautron M, Brasseur L, Baudic S, et al. Prediction of the response to repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation of the motor cortex in peripheral neuropathic pain and validation of a new algorithm. Pain. 2025;166(1):34-41. DOI: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000003297.

34. Lefaucheur JP, Nguyen JP. A practical algorithm for using rTMS to treat patients with chronic pain. Neurophysiol Clin. 2019;49(4):301-7. DOI: 10.1016/j.neucli.2019.07.014.